[해외 DS] 샌드아트와 수학의 만남, 일시적인 예술의 영원한 이야기 (3)

그림의 변형 보다 그리는 방향에 초점을 맞춘 새로운 모델 개발 샌드 아트의 사이클 구조를 보존하고, 제작 과정도 잘 반영해 수학적 개념들은 벽을 쌓기보단, 예술의 본질에 더 가까워져

[해외DS] 샌드아트와 수학의 만남, 일시적인 예술의 영원한 이야기 (2)에서 이어집니다.

마르시아 애셔는 회전, 이동, 대칭, 반전 등의 변형(transformation)이 가해진 일련의 패턴으로 모래 그림을 모델링할 것을 제안했었다. 하지만 알반 다 실바는 현장에서 제작자들의 이야기를 듣다 보니 변형이 디자인 설계에 근본적인 역할을 하지 않는다는 것을 깨달았다. 사실 그들은 변형에 상관없이 해당 디자인을 지칭하는 데 동일한 용어를 사용했었다. 따라서 실바는 샌드 아티스트들의 접근 방식을 설명할 다른 방법이 필요했다.

노드와 방향의 결합으로 더 완전해진 샌드 아트의 알고리즘

그래프는 개체(vertex) 간의 일련의 관계(edges)를 모델링하는 데 매우 유용하다. 그러나 애셔는 작품에서 관계의 본질을 고려하지 못했다. 그리드의 노드, 그래프의 정점, 간선의 곡선을 강조했기 때문에, 그녀는 아티스트가 한 지점에서 다른 지점으로 이동하는 방식을 간과할 수밖에 없었다. 반면 실바는 이들에게 선을 그리는 방향이 노드만큼이나 중요하다는 것을 포착했다.

디자이너의 손가락이 노드에서 노드로, 초기 방향에서 최종 방향으로 이동하기 때문에 두 개의 선이 한 노드에서 대각선 방향으로 교차할 때, 서로 다른 역할을 수행한다는 점을 알아냈다. 따라서 그래프로 모래 그림을 모델링하려면 그리드의 모든 노드가 하나가 아니라 각각의 방향에 할당된 두 개의 정점으로 분리해야 완성될 수 있었던 것이다.

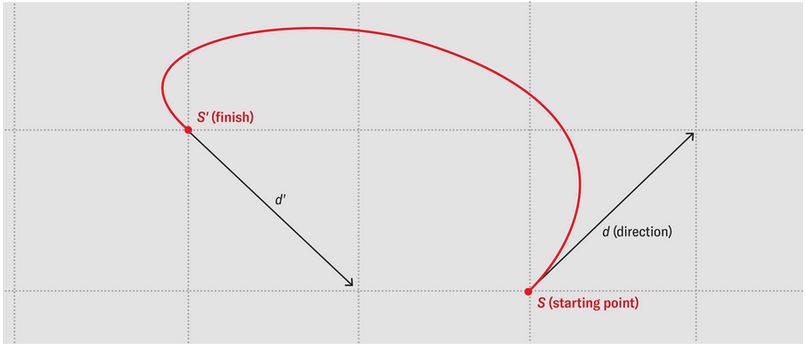

애셔가 제안한 것처럼 그리드의 노드는 S가 아닌, 방향을 함께 표현할 수 있는 (S, d)를 새로운 노드 단위로 삼아야 했다. d는 이동 방향이며, S에서 S’으로 이동하기 위해선 S 노드에서 d 방향으로 출발하여 d’ 방향으로 S’ 노드에 도착해야 한다.

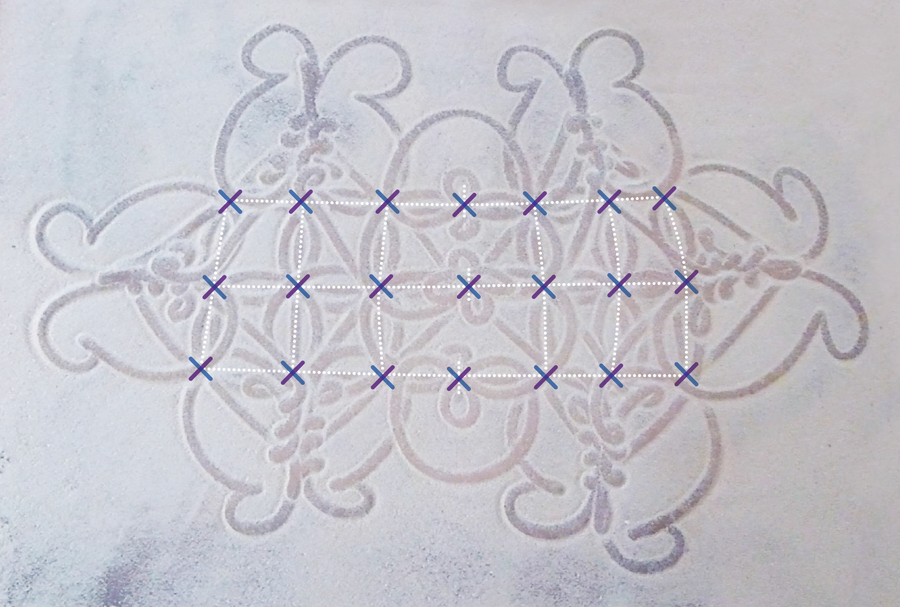

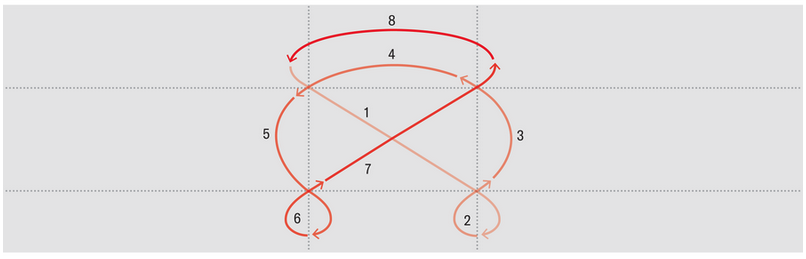

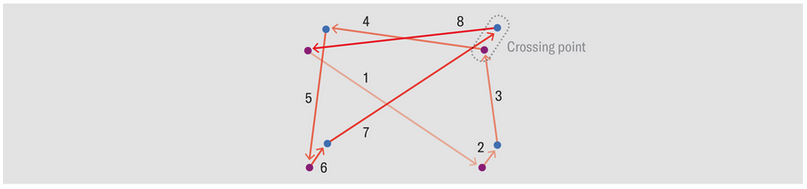

아래 곡선형 그래프는 모래 그림을 모델링한 그래프 G 이다. 선 위의 숫자는 이 선들이 그려진 순서를 나타내고 있다. 직선형 그래프는 G 그래프에서 교차하는 각 지점을 두 개의 노드로 대체한 Gmod 그래프다. 각 교차점이 두 개의 대각선 방향으로 구성되어 있다는 사실을 반영한 것으로, 보라색 또는 파란색 노드는 두 가지 대각선 방향 중 하나를 가리킨다.

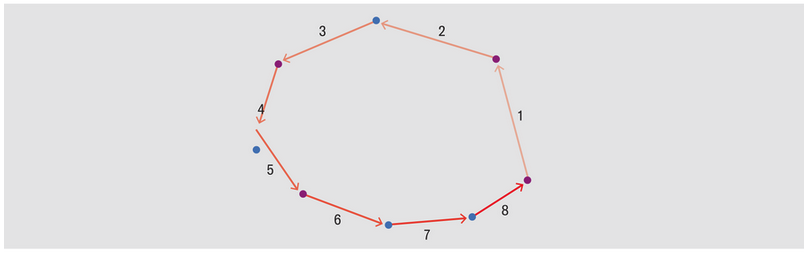

최종적으로 Gmod의 선과 꼭짓점을 펼치면 Gmod가 여전히 오일러 그래프임을 확인할 수 있다.

수학의 보편성과 확장성으로 문화 교육에 깊이를 더해야

1912년 수학자 오즈월드 베블런(Oswald Veblen)은 오일러 그래프의 또 다른 특징인 ‘베블런의 정리’를 통해 그래프를 분리된 하위 사이클들의 집합으로 재정의할 수 있는 경우에만 오일러 그래프라는 사실을 밝혀냈다. 그래프 이론에서 ‘사이클’이라는 단어는 시작과 끝 정점이 동일한 연속된 선의 시퀀스를 의미한다. Gmod 그래프의 사이클은 모래 그림의 사이클과 일치하고, 모래 그림은 하위 사이클의 집합으로도 정의할 수 있으므로 베블런의 정리를 따른다고 할 수 있다.

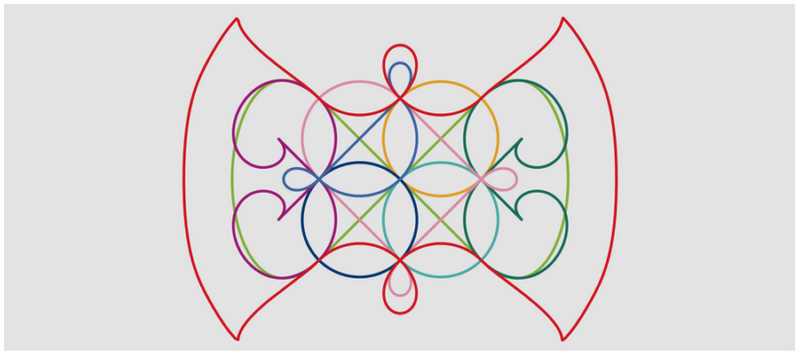

모래 그림을 오일러 그래프 정리와 베블런 정리로 해석한 일은 분명 창의적인 시도다. 하지만 수학적 개념들이 바누아투의 모래 그림을 이해하는 데 더 큰 장벽으로 작용하지는 않았을까? 실바는 수학적 해부를 통해 샌드 아트의 본질을 더 잘 드러낼 수 있다고 강조했다. 그가 수집한 60여 점의 그림을 보면 작가들이 한 사이클을 완성할 때 잠시 쉬는 것을 볼 수 있으며, 다른 경로(비슬라마어로 rod)를 찾아야 할 경우, 그림에서 사용하는 일반적인 사이클 순서를 재배열하거나 다른 분해 조합을 시도하는 경향이 있다고 전했다. 사이클을 중심으로 그림을 분해하고 조합하는 시선이 수학자나 바누아투 예술가나 근본적으로 같다는 점을 시사한다.

일부 사이클에는 고유한 이름이 있는데, 이는 아티스트에게 사이클이 일종의 재료와 같다는 것을 암시한다. 사실 그래프 사이클에 대한 이러한 초점은 바누아투 사회가 세계를 이해하는 방식을 반영하는 것처럼 보인다. 실바의 연구에서는 일부 사이클의 분해가 해당 사회가 비인간과의 관계를 생각하는 방식과 관련이 있을 수 있다고 제안했다. 한편 2010년부터 바누아투 학교에서는 모래 그림과 같은 전통 지식을 습득하는 과목이 시행되고 있으나 교육 탈식민지화 운동의 일환일 뿐, 모래 그림의 수학 개념을 연계해서 커리큘럼을 구성하지 않았다. 수학을 통해 문화 교육의 의의를 확장시키기 위해 뉴칼레도니아 대학의 교육학 박사 과정 학생인 피에르 멧산(Pierre Metsan)은 활발히 연구 중이다. 그의 연구를 통해 수학의 보편성이 샌드 아트를 그림으로만 접한 사람들에게 더 많이 알려지기를 기대해볼 수 있다.

To investigate, I sought to first refine the graph model proposed by Ascher and then determine whether computers could generate an automated breakdown of the sand drawings. Ascher had proposed modeling sand drawings with a set of patterns subjected to transformations (such as rotation, translation, symmetry and inversion). But while listening to the creators of sand drawings, I realized that transformations did not play a fundamental role in the execution of their designs. In fact, they used the same term to designate a motif, whatever its orientation on the grid. I therefore needed another way to describe the approach of these sand artists.

The artists themselves helped me in this effort. Graphs are very useful for modeling a set of relationships (edges) between objects (vertices). But in her work, Ascher did not consider the nature of these relations. By emphasizing the nodes of the grid, the vertices of the graph and the curves at the edges, she overlooked the ways in which the artist would move from one peak to another. While questioning the experts, I observed that, for them, the direction of the movement is as important as the nodes: the designer’s finger moves from node to node, from an initial direction to a final direction, so that the nodes play different roles when they are crossed, according to one or the other of the two possible diagonals.

To model the sand design with a graph, therefore, it is possible to create a graph in which every node of the grid is treated not as one but rather two vertices that are each assigned to a diagonal. We thus obtain a new graph—named Gmod—whose vertices are not the nodes S of the grid, as Ascher proposed, but instead the pairs (S, d).

In this graph, d is the direction taken, and each movement of the drawing that leaves from S in the direction d and arrives in S’ in the direction of d’ corresponds to an edge between the vertices (S, d) and (S’, d’). And this resulting Gmod graph is still Eulerian!

A Theorem Discovered in Drawings

In 1912 mathematician Oswald Veblen identified another characteristic of Eulerian graphs in what has since been called Veblen’s theorem: a graph is Eulerian if and only if it can be broken down into a union of disjoint cycles. In graph theory, the word “cycle” refers to a sequence of distinct consecutive edges whose start and end vertices are identical.

It turns out that the cycles of the Gmod graph correspond to those of a sand drawing, which can therefore be broken down as a disjoint union of cycles.

Does this approach distance us from sand drawers? I would argue that it does not. On the contrary, cycles can provide keys to better understanding their approach. Of the 60 or so drawings that I have collected, I have noticed that artists sometimes take breaks in their drawing when they complete a cycle. Moreover, when a sand drawer is forced to find another path (a rod in Bislama), they tend to rearrange the typical cycle order that they use in their drawing or to try to find another decomposition into cycles.

Finally, some cycles have vernacular names, which suggests that they are like building blocks for the artists. In fact, this focus on graph cycles also seems to echo the stories that accompany the drawings, which play a fundamental role in the way Vanuatu societies understand the world. In my research, I have also suggested that some cycle decompositions might be linked to the way these societies conceive of their relationship with nonhumans.

These results raise questions about the universality of mathematics and the form that math takes in other cultures. They open up perspectives for teaching mathematics as well. Since 2010 the acquisition of traditional knowledge such as sand drawing has been one of the objectives of Vanuatu schools, and it is part of a larger movement to decolonize education, much like efforts in Hawaii and in the French territory of New Caledonia. In the current school curriculum, however, no link is made between sand drawing and mathematics. To that end, Vanuatuan Pierre Metsan, a doctoral student in education at the University of New Caledonia, is studying whether the practice of sand drawing could support mathematics instruction. We can look forward to what he learns from this investigation in the years to come.