[해외 DS] ‘확산 모델’, 효율적인 물건 배치 가능케 해

확산 모델을 사용해 로봇이 짐을 싸는 방법을 학습 기존 방식보다 빠르고 효율적으로 짐을 싸는 데 성공 여행뿐만 아니라 다양한 분야에서 활용될 수 있어

[해외DS]는 해외 유수의 데이터 사이언스 전문지들에서 전하는 업계 전문가들의 의견을 담았습니다. 저희 데이터 사이언스 경영 연구소 (GIAI R&D Korea)에서 영어 원문 공개 조건으로 콘텐츠 제휴가 진행 중입니다.

규칙 기반에서 ‘학습 기반’으로 한 단계 도약

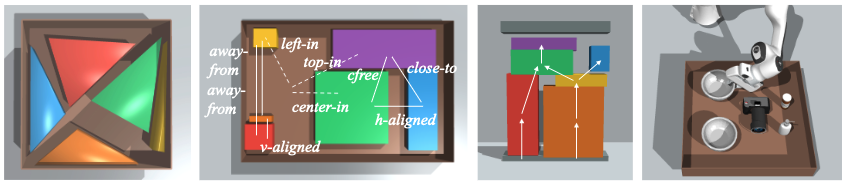

자동차 여행을 위해 짐을 싸는 것은 간단한 작업처럼 보일 수 있지만, 로봇이 학습하기에는 결코 쉬운 일이 아니다. 매사추세츠공과대학과 스탠퍼드대학의 연구팀은 ‘확산 모델(Diffusion Model)’이라는 생성형 AI의 한 형태를 사용하여 로봇이 무거운 물건이 가벼운 물건을 부수지는 않는지, 일부 물건 사이에 일정한 공간이 있는지, 로봇의 팔이 실수로 컨테이너에 부딪혀 손상되지 않는지 등 다양한 제약 조건을 준수하면서 제한된 공간에 물건을 효율적으로 배치하도록 데이터를 학습했다. 연구진은 확산 모델을 통해 로봇이 과거에 사용했던 훈련 방법보다 더 빠르게 목표를 달성할 수 있었다고 전했다.

논문의 주 저자인 매사추세츠공과대학교 박사과정 학생인 주티안 양(Zhutian Yang)은 “학습 기반은 기존 방식에 비해 제약 조건을 더 빨리 해결할 수 있으므로 학습 기반 방법을 사용했다”라고 말했다. ‘학습 기반’ 접근 방식은 AI 프로그램이 학습 데이터와 원하는 결과 사이의 패턴을 식별하여 자율적으로 학습할 수 있도록 하는 것이다. 이는 엄격하게 지정된 규정 내에서만 작동해야 했던 이전의 ‘규칙 기반’ 프로그램과는 확연히 다르다. “확산 모델은 다양한 해결책을 샘플링하고 모든 제약 조건을 공동으로 만족시키는 데 매우 효율적인 방법이다”라고 양은 강조했다.

Continuous Constraint Solvers

확산 모델 순차적 작업 한계 극복해, “이제는 동시 작업”

이번 연구에 참여하지는 않았지만 비슷한 연구 분야에서 일하고 있는 조지아공과대학교의 AI 로봇공학 조교수 아니메쉬 가그(Animesh Garg)는 “자율 포장 공정은 줄곧 어려운 문제였다”라고 언급했다. “머신러닝이 없으면 계산 집약적인 온라인 3D 패킹 프로그램이 필요하다. 해당 프로그램의 코딩된 수준에 따라 해결할 수 없는 상황이 발생할 수도 있는 규칙 기반 기술을 사용할 수밖에 없었다”라고 덧붙였다.

이전에는 앞서 언급한 제약 조건 내에서 배치 최적화를 달성하려면 차례대로 작업해야 했다. 가능한 배치 구성을 개발하고 한 번에 하나의 제약 조건에 대해 각각 테스트한 다음, 다른 제약 조건과의 충돌 여부를 확인해야 했다. 이러한 시행착오를 거치는 방식은 특히 패킹할 항목이 많아 테스트해야 할 작업이 늘어날 때 과부하가 발생한다. 반면에 새로운 연구에서는 확산 모델을 통해 로봇이 개별 제약 조건을 위한 여러 머신러닝 모델을 동시에 탐색할 수 있게 되었다. 개별 모델을 통해 로봇은 문제를 다각도에서 파악할 수 있었고, 거의 즉각적으로 모든 제약 조건을 한꺼번에 고려했다. 그 결과 이전 기술보다 훨씬 더 효과적인 배치 구성을 효율적으로 찾을 수 있게 되었다. 또한 이 연구의 확산 모델은 학습한 정보 이상으로 더 많은 수의 품목에 적용되는 낯선 제약 조건 조합을 해결하기도 했다.

인간의 선입견 뛰어넘고 확장 분야도 넓어

연구팀은 학습 알고리즘이 대부분 사람의 직관과 어떻게 일치하는지, 또는 무엇이 다른지도 살펴봤다. 인간은 가장자리에 먼저 물건을 배치하는 습관이 있는데, 물건이 많으면 항상 왼쪽 아래부터 물건을 놓는다. 물건을 쌓을 때는 한쪽에서 다른 쪽까지 쌓지 않고 층층이 고르게 쌓아 올리는 경향이 있었다. 인간의 관점에서 보면 합리적으로 보일 수 있지만, 인간의 선입견이 없는 학습 기반 로봇은 다양한 해결책을 자유롭게 발견할 수 있는 장점이 있다. 인간보다 더 빠르고 효율적으로 짐을 꾸릴 수 있는 능력을 갖춘 로봇은 자동차 여행을 위한 짐칸 정리 외에도 다양한 분야에서 활용될 수 있다. 예를 들어 배송업체에서 서로 다른 물품을 하나의 컨테이너에 포장하거나 제약회사에서 다양한 약품을 병원으로 대량 배송하는 작업에 적합하다.

현재 연구팀은 로봇이 분산형 의사 결정을 내릴 수 있게 하기 위해 노력하고 있다. 여기에는 로봇에게 제약 조건 내에서 짐을 싸도록 가르치는 것뿐만 아니라, 지속적으로 변화하는 변수(예: 방을 이동하면서 동시에 물건을 포장해야 할 때)에서도 그렇게 하도록 훈련하는 것이다. 또한, 자연어 명령을 추가 입력으로 받아들여 사용자 편의성을 높일 수 있도록 모델을 확장하는 방향도 고려하고 있다고 전했다.

AI Teaches Robots the Best Way to Pack a Car, a Suitcase—Or a Rocket to Mars

Robots that can fit multiple items into a limited space could help pack a suitcase or a rocket to Mars

Packing the car for a road trip might seem like a straightforward enough task, but it’s never been an easy one for robots to learn—until a new study turned the robot training over to artificial intelligence. The implications of this research go far beyond a well-packed trunk and could eventually impact things ranging from how we manage our homes to how we colonize Mars.

Using a form of generative AI known as a “diffusion model,” a team of researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Stanford University trained robots to pack items into a limited space while adhering to a range of constraints: human concerns such as making sure that heavier items didn’t crush lighter ones, that some items had a certain amount of space between them, that a robot’s arm didn’t accidentally strike the container and damage it, and so on. The diffusion model helped the robots accomplish this faster than training methods used in the past, the researchers say.

“We want to have a learning-based method to solve constraints quickly because learning-based [AI] will solve faster, compared to traditional methods,” says M.I.T. Ph.D. student Zhutian “Skye” Yang, lead author of a paper detailing the study, which was recently released ahead of peer review on preprint server arXiv.org. A “learning-based” approach involves allowing an AI program to learn autonomously by identifying patterns between training data and the desired output. This differs from previously tested “rule-based” programs, which are more limited as they must behave within a strictly coded set of regulations. “The diffusion model is a very good method for sampling different solutions to a problem and jointly satisfying all of the constraints,” Yang says.

Autonomous packing “has been a challenging problem,” says Animesh Garg, an assistant professor of AI robotics at the Georgia Institute of Technology, who was not involved in the new study but works in a similar research area. “Without machine learning, the solution involves computationally intensive online 3-D bin packing”—a rule-based technique that “can even be unsolvable” depending on a program’s coded limitations.

Previously, for a robot to solve a packing problem within the aforementioned constraints, it would have to work sequentially. It would develop possible packing configurations and test each against one constraint at a time, then check for conflicts with the other constraints. This trial-and-error method proved too slow, especially when there were more items to pack—and therefore more actions to test. In the new study, the diffusion model, on the other hand, allowed a robot to simultaneously explore an array of machine-learning models, each representing an individual constraint. The sum total of these models afforded the robot a more thorough view of the problem, enabling it to consider all constraints at once, almost instantaneously. As a result, many more successful packing configurations were found faster than they had been with previous techniques. The study’s diffusion method also proved capable of solving new combinations of constraints that were applied to a larger number of items—beyond what the model experienced during training.

“Packing with robots is incredibly hard yet transformational,” Garg says. “This work enables robots to start ‘thinking’ on the fly and achieve very good, if not optimal, solutions quickly.”

“It’s a type of optimization problem,” Yang says. “With the learning-based method, we’re happy to see that if we train on the small problems, it can generalize to solving problems with a larger number of objects or a larger set of constraints.”

The study team also looked at how its learning algorithm aligned with—or diverged from—most people’s intuition about how to pack. Humans “have heuristics of packing things to the edge first,” Yang says. “If you have a lot of things, you always pack them to the bottom left-hand side. Or if you are stacking things, you place things evenly, layer by layer, instead of all the way up one side and then the other.” While these heuristics may seem logical from a human perspective, learning-based robots without our preconceptions are free to discover novel solutions.

But by analyzing data ahead of time and keeping likely end solutions in mind before you start packing, you eliminate the need for trial and error. To pack multiple objects into a limited space—think a car trunk or a suitcase—like one of the study’s AI-powered robots, there are three steps. First, ponder ahead of time what you know about packing and what constraints must be met. Next, imagine solutions before you start loading objects. And finally, pack toward that ideal solution, not necessarily by following your intuition.

“There could be many solutions” that may not be intuitive, Yang says. “And you can change the plan as you go.”

Robots gaining an ability to pack faster and more efficiently than their human counterparts has applications far beyond road trips. “I want to have robots in the kitchen helping with housework,” Yang explains. “I just went to an industry robotic company to give a talk, and they are very interested in using this algorithm to pack for their customers.” For instance, she suggests the technique could help shipping companies pack disparate items into a single container or drug companies deliver a wide variety of medications to hospitals in bulk. The possibilities even transcend the planet. “If you’re going to Mars, you can have a robot decide how best to pack the resources,” Yang suggests.

Garg agrees the implications may be far-reaching. “Robotic packing and placement will enable a very large set of open-world robotic skills,” he says. More studies are needed, however. “This work has very impressive results, but it is still a few steps from considering the problem ‘solved,’” Garg says. “I hope that this work will galvanize the community to make quick progress in this domain.”

Now the team at M.I.T. and Stanford is working to make its robots even more capable at making “discrete decisions.” This involves not only teaching a robot to pack within constraints but also training it to do so within continuously shifting variables—for example, when tasked with packing items while simultaneously moving through a room.

So the next time you’re packing, consider doing it like a robot to optimize results. Before long, you might simply leave it entirely up to the machines.