[해외 DS] ‘하이퍼볼릭 밴드’, 양자 수학 이론이 재즈 콘서트가 되기까지

수학자와 작곡가의 협업으로 양자-재즈 재탄생 쌍곡선 밴드 이론을 기반으로 한 재즈 음악 수학적 개념과 음악적표현의 유기적 결합

[해외DS]는 해외 유수의 데이터 사이언스 전문지들에서 전하는 업계 전문가들의 의견을 담았습니다. 저희 데이터 사이언스 경영 연구소 (GIAI R&D Korea)에서 영어 원문 공개 조건으로 콘텐츠 제휴가 진행 중입니다.

2021년, 두 명의 진취적인 공동 연구자들이 대담한 실험을 시작했다. 수학자이자 수리물리학자인 스티븐 라얀(Steven Rayan)과 프리랜서 작곡가, 피아니스트, 트롬본 연주자인 제프 프레슬라프(Jeff Presslaff)는 2년 동안 한 가지 큰 질문에 답하기 위해 준비했다. 수리물리학 논문을 음악으로 번역할 수 있을까? 그리고 듣기에도 좋을까?

지난 9월 라얀과 프레슬라프는 그들의 아이디어로 만든 Math + Jazz: Sounds from a Quantum Future 연주회를 개최했다. 서스캐처원대학교 연구원인 라얀과 캐나다 위니펙에 있는 프레슬라프가 이메일로 처음 만난 지 2년 만에 15명의 ‘하이퍼볼릭(Hyperbolic, 쌍곡선) 밴드’ 음악가들을 모아 서스캐처원대에서 5개 섹션으로 구성된 콘서트를 열었다. 각 섹션은 라얀의 논문을 참고한다.

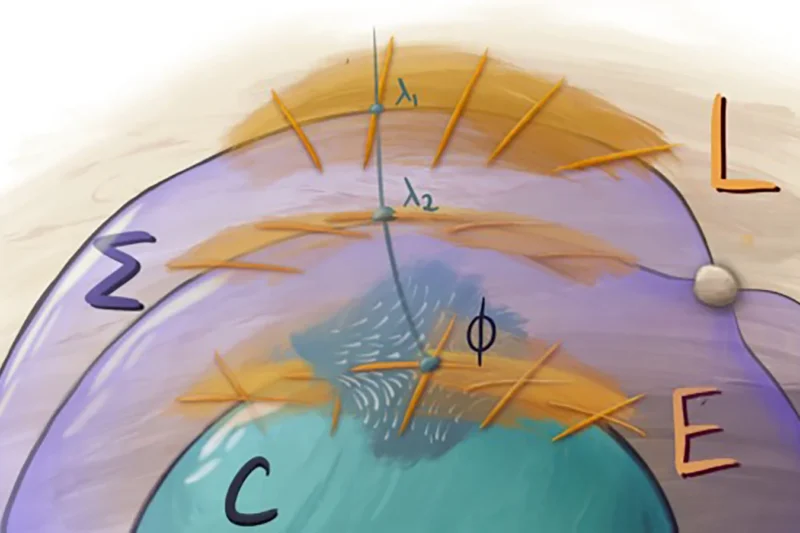

음악 연주와 강의를 겸한 이 콘서트는 만석을 채웠다. 강의는 논문의 과학적 개념이 어떻게 음악으로 변환되었는지 설명하고, 슬라이드 쇼에서는 엘리엇 킨즐(Elliot Kienzle)의 하이퍼볼릭한 그림 예술을 선보였다. 그러나 콘서트를 성공적으로 개최하는 것은 쉬운 일이 아니었다. 참여 뮤지션 대부분이 지역 출신이 아니었기 때문에 밴드는 콘서트 전날까지 실제로 함께 리허설을 해본 적이 없었다고 라얀은 전했다.

쌍곡선 밴드 이론

이 음악은 라얀이 앨버타대학의 조셉 마체코(Joseph Maciejko)와 함께 쓴 2021년 사이언스 어드밴시스(Science Advances) 논문 ‘쌍곡선 밴드 이론’을 기반으로 한다. 그들의 목적은 연구자들이 물질의 에너지 준위와 이를 구성하는 원자를 고찰하기 위해 사용하는 밴드 이론이, 불규칙하고 뒤틀린 배열을 가진 쌍곡면 물질을 설명하기 위해 재구성될 수 있는지를 탐구하는 것이었다.

밴드 이론에서는 물질의 에너지 준위가 그들이 속한 물질 위에 떠 있는 시트 모양의 밴드에 포함되어 있다고 본다. 이 그림자 같은 밴드가 물질의 양자적 성질을 나타내며, 밴드 간의 상호작용이 물질의 움직임에 영향을 미친다.

라얀과 마체코는 유클리드의 ‘평행선 공준‘을 깨는 기묘한 기하학적 영역인 쌍곡선 기하학의 세계에서 작동하는 밴드 이론을 발견하는 데 성공했다. 유클리드의 ‘제 5공준’이라고도 불리는 이 법칙은 다음과 같다. 어떤 직선이 주어졌을 때, 그 직선 위에 있지 않은 어떤 점에 대해서도 그 점을 지나고 원래의 직선과 평행한 직선은 하나뿐이다. 하지만 쌍곡선 위에서는 최소 두 개의 선이 그 점을 지나고 주어진 선과 평행하게 된다.

“이 연구는 소재, 특히 양자 소재의 안팎을 뒤집어 재구성함으로써 소재를 설계하는 완전히 새로운 접근 방식이다.”라고 라얀은 말한다. 이 접근법은 소재의 밴드 구조를 변경하여 재료의 특성에 기대했던 변화를 불러온다. “재료는 평소와 다른 이국적인 모양을 취할 수 있다.”

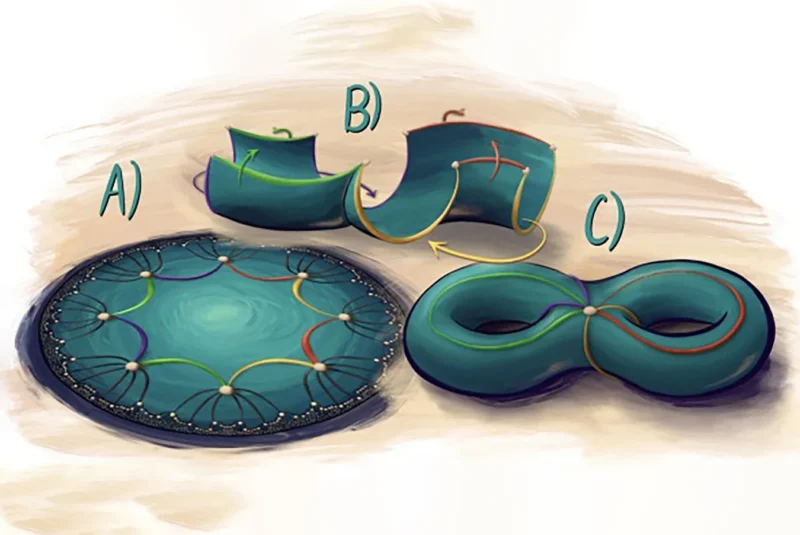

예를 들어 곡면을 팔각형 타일 모양으로 덮어, 모양 사이에 간격이 없도록 하는 것과 같다. 인간의 눈에는 팔각형의 가장자리가 구부러져 보이고 모양이 다른 크기로 보인다고 라얀은 언급했다. 하지만 “만약 우리가 세상을 쌍곡선으로 보는 다른 눈(곤충과 같은 복안)을 가지고 있다면 (팔각형은) 모두 똑같이 보일 수 있다”라고 그는 말했다.

이 연구는 다른 연구자들도 주목했다. 이 논문에 참여하지 않은 토론토대학의 수학자 마이클 그로첸치(Michael Grochenich)는 “이 논문의 저자들이 발굴한 재료과학과 대수 기하학의 연결고리에 깊은 인상을 받았다”고 말했다.

라얀은 자신의 발견을 양자 컴퓨팅과 같은 파괴적인 응용 잠재력을 가진 희귀 물질 연구에 적용할 수 있다는 사실에 흥분했다. “누군가가 이토록 구체적인 성격의 방법론으로 중요한 응용 사례를 보여주어 기쁘다”고 그로첸니히는 말한다. 그는 이 논문이 “순수 수학자들에게 편안한 영역에서 조금 벗어나 지금까지 알려지지 않은 영역을 탐구하도록 초대하는 것”이라고 덧붙였다.

음악으로의 전환

수학 콘서트를 만드는 것은 그 자체로 연구의 파괴적인 응용이다. “인상주의적인 음악이 되기를 원하지 않는다”라고 프레슬래프는 강조했다. “수학에 정말 충실한 음악이길 바랐다. 피상적으로만 느껴지는 학제 간 프로젝트를 너무 많이 보았는데 과학 분야는 엄격할지 몰라도 예술 분야는 엄격하지 않기 때문인 것 같다.” 라얀은 그의 목표에 공감했다. “수학이나 과학에서 어느 정도 영감을 받은 음악을 만드는 것이 아니라, 수학의 단어 하나하나, 각각의 방정식을 음악의 형태로 재현하는 것을 목표로 삼았다”라고 그는 밝혔다.

하지만 이러한 도전을 받아들이기 위해서는 두 전문가가 자신의 영역을 벗어나 서로의 전문 분야에서 새로운 개념을 배워야 했다. 프레슬라프는 선형대수학과 위상기하학에 몰두해 연구 논문의 내부 구조를 파악하고, 라얀은 “프레슬라프가 가져온 고도의 음악적 아이디어를 최대한 이해하려고 노력했다.

프레슬라프가 작곡을 시작할 때까지 두 사람은 약 1년 반 동안 아이디어를 주고받았다. 라얀은 “9월 20일 공연 전날까지 제프를 한 번도 직접 만난 적이 없었다는 것이 놀랍다”라고 전했다. “팬데믹과 거리상의 이유로 모든 것이 줌(Zoom)을 통해 이루어졌다. 순전히 온라인으로만 작업할 수 있다는 점이 정말 매력적이었다.”

이중 푸가와 무한한 형태

라얀과 프레슬라프가 논문의 주요 아이디어를 그대로 재즈 음악으로 전환하는 장대한 목표를 달성했는지는 정확히 파악하기 어렵다. 수학 연구와 달리, 그들이 목표를 달성했다는 ‘증명’이 존재하지 않기 때문이다. 그런데도 그들은 결과에 만족했다. “공연 6주 전까지만 해도 이 작업을 완수할 수 있을지 확신할 수 없었다”라고 라얀은 그 당시의 솔직한 심정을 밝혔다.

하이퍼볼릭 밴드의 연주자이자 볼티모어에서 활동하는 비올라 연주자 샤 사디코프(Shah Sadikov)는 공연의 하이라이트는 프레슬라프가 구현하기 매우 어려운 음악 기법인 ‘이중 푸가’를 사용하여 ‘무한한 형태’를 구축하는 과정을 표현할 때였다고 사디코프는 전했다. 수학적으로는 시작도 끝도 없는 물체를 만드는 것을 의미했다고 그는 말했다. 음악적으로 이중 푸가를 만드는 것은 “어떤 아이디어를 곡의 기초로 삼고, 그 위에 똑같은 아이디어를 조금 후에 배치하는 것”이라고 한다. “이렇게 아이디어의 층을 만들어서 같은 음악적 아이디어를 거꾸로 뒤집거나 앞뒤로 옮기는 것”이라고 그는 설명했다.

라얀에게 하이라이트는 소위 입자와 파동의 이원성, 또는 쌍곡선 밴드 이론에서 위치와 운동량의 이원성에 대한 프레슬라프의 음악적 해석을 듣는 것이었다. 이 맥락에서 운동량은 위치보다 더 많은 차원을 가질 수 있다. “우리는 팔각형 쌍곡선 격자를 기반으로 한 가장 단순한 재료에서, 예를 들어 2차원에서 4차원으로의 전환을 음악으로 포착하고 싶었다.”

“(프레슬라프가) 음악에 여분의 목소리를 도입하고 여분의 자유도, 여분의 2차원으로의 갑작스러운 점프를 포착하려고 노력하는 것을 듣는 것은 나에게 감동적인 경험이었다”라고 라얀은 말한다. “그의 설명 후 청중들이 여분의 목소리를 들으려고 노력하는 것을 보는 것이 좋았다.”

콘서트에는 또 하나의 예술적 요소가 있었는데, 바로 킨즐이 직접 그린 그림이었다. 현재 캘리포니아대학교 버클리캠퍼스의 대학원생인 킨즐은 메릴랜드대학교 칼리지파크의 학부생 시절, 라얀과 함께 작업한 관련 연구 프로젝트를 위해 수학적 개념을 예술로 제작하는 일을 맡았었다. “이것은 시각적 렌즈를 통해 이야기를 전달하려는 시도였다”라고 라얀은 설. 콘서트에서 이 그림들은 음악과 언어로 수학과 과학에 대한 설명을 보완하는 데 도움이 되었다.

라얀은 음악과 예술의 렌즈를 통해 이 작품을 재해석하는 것이 이 작품을 완성하는 방법이라고 생각했다. 그의 논문에서 다루고 있는 많은 수학적, 과학적 개념들은 예술의 세계에서 아이디어를 차용하고 있다. 예를 들어, “쌍곡선의 기울기는 네덜란드 그래픽 아티스트 M.C. 에셔의 상징적인 목판화를 떠올리게 한다”라고 그는 얘기했다. 라얀은 수학적 관점과 예술적 관점을 융합하는 새로운 방법을 계속 탐구해 ‘예술로 환원’하는 동시에 자신의 연구에 새로운 통찰력을 불어넣고 싶다고 한다.

How Quantum Math Theory Turned into a Jazz Concert

A mathematician and a musician collaborated to turn a quantum research paper into a jazz performance

In 2021 an unconventional pair of collaborators embarked on a bold experiment. For two years Steven Rayan, a mathematician and mathematical physicist, and Jeff Presslaff, a freelance composer, pianist and trombonist, prepared to answer one big question: Could they translate a mathematical physics research paper directly into music? Moreover, would their musical creation sound good?

In September Rayan and Presslaff released their brainchild, “Math + Jazz: Sounds from a Quantum Future.” Exactly two years to the date that Rayan, a researcher at the University of Saskatchewan, and Presslaff, who’s based in Winnipeg, Canada, first connected over e-mail, they gathered a 15-piece “hyperbolic band” of musicians to perform the five-section concert at the University of Saskatchewan. Each section corresponded to a portion of Rayan’s research article.

Part musical performance and part lecture, the concert was played to “a packed house,” Rayan says. The lecture portion dissected the paper’s scientific concepts and illustrated how those ideas were transmogrified into music. Some of the illustrations were literal: the slideshow featured hyperbolic art created by Elliot Kienzle.

Pulling off the concert was no easy feat. Because many of the musicians weren’t local, the band hadn’t rehearsed the music together in person until the night before the concert, Rayan notes.

HYPERBOLIC BAND THEORY

The music was based on Rayan’s 2021 Science Advances article “Hyperbolic band theory,” which he wrote with Joseph Maciejko of the University of Alberta. Their objective was to explore whether band theory—which researchers use to consider the energy levels of materials and the atoms that they’re made of—could be reformulated to explain hyperbolic materials, which have irregular, warped arrangements.

In band theory a material’s energy levels are thought of as being contained in sheetlike bands hovering above the materials they belong to. These shadowy bands represent the material’s quantum properties, and interactions between these bands have consequences for the material’s behavior.

Rayan and Maciejko succeeded in discovering a band theory that works in the wonky world of hyperbolic geometry, a strange geometrical realm that breaks Euclid’s “parallel postulate.” Also called Euclid’s fifth postulate, this rule tells us the following: Suppose you’re given a line. For any point that isn’t on that line, there will be only one line that both goes through that point and is parallel to the original line. In hyperbolic land, a minimum of two lines will go through the point while also being parallel to the given line.

The research “is a whole new approach to designing materials—especially quantum materials—by re-engineering their geometry from the inside out,” Rayan says. The approach involves altering the material’s band structure to create the desired changes in the material’s properties. “They can take on unusual, exotic geometries,” he says.

This might look like, for instance, covering a curved surface by tiling it with octagons so that there aren’t any gaps between the shapes, which are nonoverlapping. To human eyes, the edges of these octagons appear curved, and the shapes look like they are different sizes, Rayan notes. But “if you had a different kind of eye that sees the world in a hyperbolic way—maybe insectlike compound eyes—[the octagons] might all look the same to you,” he says.

The work received a lot of attention from other researchers. “I’m very impressed by the connection between material science and algebraic geometry which was unearthed by the authors of this paper,” says Michael Groechenig, a mathematician at the University of Toronto, who wasn’t involved with the article.

Rayan is excited to apply his findings to studying unusual materials with the potential for “disruptive applications,” such as in quantum computing. “It’s rather delightful to see someone exhibit an important application of these methods of such a concrete nature,” Groechenig says. The paper is “an invitation for us pure math folks to leave our comfort zone a little and to explore hitherto uncharted territory,” he adds.

TRANSLATING TO MUSIC

Creating a mathematical concert is its own kind of disruptive application of the research. “I didn’t want [the music] to be impressionistic,” Presslaff says. “I wanted it to be really true to mathematics…. I’ve just seen too many cross-disciplinarity projects that just strike me as superficial. The science side might be rigorous, and the art side is very not rigorous.”

Rayan agreed with that goal. “I had a commitment to not just producing music that was somehow loosely inspired by the math and the science but rather somehow retelling the mathematics word for word, equation for equation, in a musical form,” he says.

But embracing that challenge also required that both experts leave their comfort zones and learn concepts from each other’s areas of expertise. Presslaff immersed himself in topics from linear algebra and topology that helped illuminate the inner workings of the research paper. Rayan dove into “trying to understand, as much as possible, the advanced musical ideas [Presslaff] brought to the table.”

The pair exchanged ideas for approximately 18 months before Presslaff even began writing the music. “It’s amazing that I never met Jeff in person until the day before the performance on September 20,” Rayan says. “It was all on Zoom because of the pandemic and because of distance. It was a fascinating way of working—that we could accomplish this even through purely virtual means.”

DOUBLE FUGUES AND INFINITE SHAPES

It’s tricky to pinpoint whether Rayan and Presslaff met their grand objective: to convert the main ideas from Rayan’s paper directly into jazz music. Unlike in mathematics research, there is no “proof” that they accomplished their goals. Still, the duo is pleased with their result. “Getting it done was just never a certain thing until even, say, six weeks before the performance,” Rayan says.

Hyperbolic Band performer Shah Sadikov, a Baltimore-based violist, says a highlight of the concert was when Presslaff used a double fugue, a musical technique that’s “very difficult to implement,” to represent the process of building an “infinite shape,” Sadikov says. Mathematically, that meant creating an object with “no beginning, no end,” Sadikov says. Musically, creating a double fugue involves making “one idea the foundation of the musical piece and then you take the exact same idea [and] you place it a bit later on top of it,” and so on, he says. “You create these layers of ideas. And then you can use counter ideas to that, either taking the same musical idea [and] putting it backwards or upwards,” he notes.

For Rayan, a highlight was hearing Presslaff’s musical take on “the so-called particle-wave duality or the position-momentum duality in hyperbolic band theory.” In that context, momentums can take on more dimensions than positions can. “We wanted to capture in the music the jump from, say, two dimensions to four dimensions in the simplest of these materials, which are based on octagonal hyperbolic lattices,” Rayan says.

“Hearing [Presslaff’s] attempts at introducing extra voices in the music that capture the extra degrees of freedom, the sudden jump to two extra dimensions, was a moving experience for me,” Rayan says. “I loved watching the audience try to hear those extra voices after [his] explanation of them.”

The concert included one other artistic element: Kienzle’s hand-drawn illustrations. Now a graduate student at the University of California, Berkeley, Kienzle created the mathematical art for a related research project that he and Rayan worked on while he was an undergraduate student at the University of Maryland, College Park. “This was an attempt to tell the story through a visual lens,” Rayan says. In the concert those illustrations helped enhance the musical and verbal explanations of the math and science.

Rayan sees reinterpreting this work through musical and artistic lenses as a way of bringing it full circle. Much of the mathematical and scientific concepts featured in his papers borrow ideas from the world of art. For instance, “hyperbolic tilings are very reminiscent of” Dutch graphic artist M. C. Escher’s iconic woodcuts, he notes. Rayan plans to continue exploring new ways of fusing mathematical and artistic perspectives to “give back to art” while also sprouting new insights for his research.