[해외 DS] 생성형 AI 모델 학습에 사용되고 있는 개인 정보, 이대로 괜찮을까

학습 데이터 출처 비공개, "대략적인 경로 파악은 가능해" 프롬프트에 민감 정보 보호 기능 있지만 '설득'할 수 있어 데이터 삭제 요청도 무시, 사실상 유명무실한 규제

[해외DS]는 해외 유수의 데이터 사이언스 전문지들에서 전하는 업계 전문가들의 의견을 담았습니다. 저희 데이터 사이언스 경영 연구소 (GIAI R&D Korea)에서 영어 원문 공개 조건으로 콘텐츠 제휴가 진행 중입니다.

생성형 인공 지능은 예술가와 작가들의 큰 공분을 샀다. ‘재주는 곰이 부리고, 돈은 왕서방이 번다’라는 속담이 틀린 것이 하나도 없다. OpenAI, Meta, Stability AI를 비롯한 주요 AI 개발사들은 현재 이와 관련하여 여러 건의 소송에 직면했다. 학습 데이터의 출처를 밝히지 않았기 때문에 작가들은 독립적인 수사에 의존하는 경우가 대다수다. 예를 들어 지난 8월 Atlantic은 Meta가 17만 권 이상의 해적판 및 저작권이 있는 도서가 포함된 Books3라는 데이터 세트를 기반으로 대규모 언어 모델(LLM)을 학습시켰다는 사실을 발견했다고 보도했다.

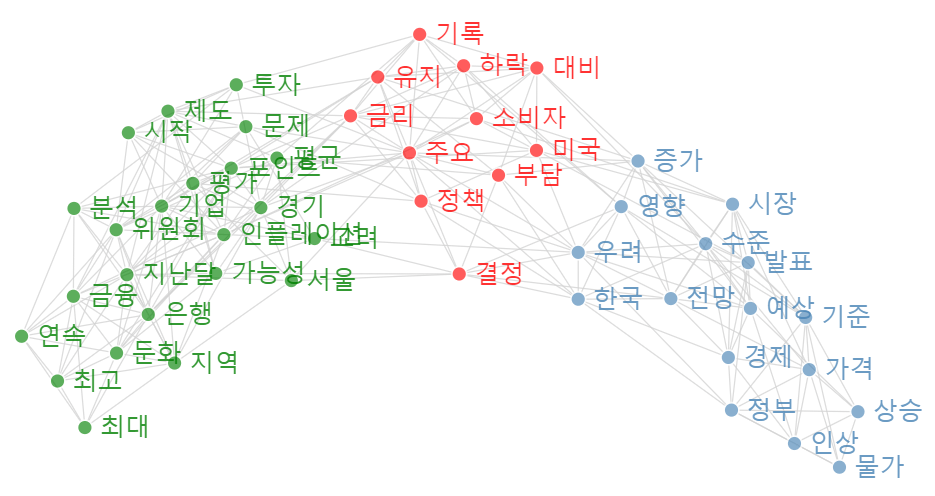

학습 데이터에는 책 외에도 다양한 데이터가 포함되어 있다. 개발자들은 점점 더 큰 규모의 AI 모델을 구축하기 위해 인터넷에서 검색할 수 있는 더 많은 정보들을 무분별하게 긁어모았다. 이는 저작권을 침해할 가능성이 있을 뿐만 아니라 온라인에서 정보를 공유하는 수십억 명의 개인 정보를 위협할 수 있다. 또한 중립적이어야 할 모델이 편향된 데이터로 학습될 수 있다는 의미이기도 하다. 기업이 학습 데이터를 어디서 얻는지 정확히 파악하기는 어렵지만 대략적인 경로는 유추할 수 있다.

학습 데이터의 다양한 출처 추정 및 수집 방법

LLM은 가장 먼저 인터넷에 공개된 데이터에 의존한다. 개발자들은 인터넷에서 데이터를 분류하고 추출하는 자동화 도구를 만들어서 학습 데이터를 축적한다. 웹 ‘크롤러(crawler)’는 URL에서 URL로 이동하면서 데이터의 위치 정보를 분류 및 저장하고 웹 ‘스크래퍼(scraper)’는 해당 링크의 데이터를 직접적으로 추출하는 방식이다. 구글은 검색 엔진을 구동하기 위해 이미 웹 크롤러 시스템을 구축해서 사용하고 있지만 다른 회사들은 OpenAI의 GPT-3를 학습하는 데 사용한 커먼 크롤(Common Crawl)같은 도구나 이미지와 함께 링크와 캡션이 제공되는 대규모 인공 지능 오픈 네트워크(Large-Scale Artificial Intelligence Open NetWork, LAION)의 데이터베이스를 주로 활용한다. LAION(Stable Diffusion의 트레이닝 세트 일부였다)을 AI 자원으로 사용하려는 회사는 콘텐츠를 직접 내려받아야 하는 번거로움이 있다.

웹 크롤러와 스크래퍼는 로그인이 필요한 페이지가 아닌 거의 모든 곳에서 데이터에 쉽게 접근할 수 있다. 비공개로 설정된 소셜 미디어 프로필은 포함되지 않지만 검색 엔진에서 볼 수 있거나 사이트에 로그인하지 않고도 볼 수 있는 데이터(예: 공개 LinkedIn 프로필)는 모두 수집 대상이다. 그리고 블로그, 개인 웹페이지, 회사 사이트 등 웹 스크랩에 절대적으로 포함되는 것들이 있다. 예상대로 인기 있는 사진 공유 사이트인 Flickr, 온라인 마켓플레이스, 유권자 등록 데이터베이스, 정부 웹페이지, Wikipedia, Reddit, 연구 자료 저장소, 뉴스 매체 및 학술 기관의 모든 것이 포함된다. 또한 해적판 콘텐츠 모음집과 웹 아카이브에는 삭제된 데이터가 여전히 포함되어 있는 경우가 많다. 스크랩된 데이터베이스는 사라지지 않기 때문에 주기적으로 학습 데이터를 업데이트하는 기업이라면 해당 사이트나 게시물이 삭제되었는지 여부와 관계없이 그들의 데이터 베이스에 영원히 살아 남게 된다.

심지어 일부 데이터 크롤러와 스크래퍼는 유료 계정으로 위장하여 페이 월(paywall)을 통과할 수 있다고 알려져 있다. 워싱턴 포스트와 앨런 연구소의 공동 분석에 따르면, 유료 뉴스 사이트는 Google의 C4 데이터베이스(Google의 LLM T5 및 Meta의 LLaMA 학습에 사용됨)에 포함된 상위 데이터 소스 중 하나다. 언론사들이 애써 만들어 놓은 로그인 월과 페이월에 자동문이 생긴 꼴이다.

웹 스크래퍼는 때로 의외의 데이터도 수집하곤 한다. 한 예술가가 자신의 사적인 진단 의료 이미지가 LAION 데이터베이스에 있다는 사실을 발견한 사례가 알려졌다. 아르스 테크니카(Ars Technica)의 보도로 해당 아티스트의 계정을 확인한 결과, 같은 데이터 세트에 수천 명의 다른 사람들의 의료 기록 사진도 포함되어 있었다. 병원의 내부망에서만 조회가 가능해야 할 민감한 개인정보가 어떻게 LAION에 저장됐는지 정확한 이유를 알 수 없지만, 개인 정보 설정이 느슨해지는 틈을 타 유출과 침해가 빈번하게 발생한다고 업계 관계자들은 지적했다. 공용 인터넷에 공개되지 않아야 할 정보도 학습에 사용되는 이유다.

이러한 웹 스크랩 데이터 외에도 AI 회사는 의도적으로 자사 내부 데이터를 모델 학습에 통합했다. OpenAI는 챗봇과의 사용자 상호 작용을 기반으로 모델을 미세 조정하고, 메타는 자사의 최신 AI가 부분적으로 페이스북과 인스타그램 ‘공개’ 게시물을 학습에 사용했다고 밝혔다. 메타가 정의하는 공개 데이터의 범위는 다소 불분명하다. 소셜 미디어 플랫폼 X(전 트위터)도 같은 작업을 수행할 계획이라고 전했다. 아마존 역시 고객의 알렉사 대화에서 얻은 음성 데이터를 사용해 새로운 LLM을 훈련할 것이라고 말했다.

그러나 기업들은 최근 몇 달 동안 데이터 세트의 세부 정보를 공개하는 데 있어서 점점 더 조심스러워지고 있다. 메타는 LLaMA의 첫 번째 버전보다 LLaMA 2가 출시되었을 때 데이터에 관한 기술 비중이 눈에 띄게 줄었다. 구글 역시 최근 발표한 PaLM2 AI 모델에 데이터 소스를 명시하지 않았으며, 이전 버전의 PaLM보다 훨씬 더 많은 데이터가 PaLM2 훈련에 사용되었다는 것 외에는 구체적인 내용을 밝히지 않았다. OpenAI는 경쟁사에 대한 견제를 이유로 꼽으며 GPT-4의 훈련 데이터의 세부 정보를 공개하지 않겠다고 입장을 표명했다.

대부분의 생성형 AI 서비스는 개인 식별 정보를 공유하지 못하도록 차단하는 기능이 있지만, 이마저도 우회하는 방법이 여러 차례 입증된 전력이 있다. 기업에서 데이터 출처를 공개하지 않는 이상 개인 정보 유출은 단순히 ‘환각’ 문제로 치부될 가능성도 있다. 한편 커먼 크롤과 같은 데이터 세트에는 백인 우월주의 웹사이트와 혐오 발언도 어렵지 않게 찾아볼 수 있다. 덜 극단적이지만 편견을 조장하는 콘텐츠도 많다. 게다가 온라인에는 수많은 포르노 콘텐츠가 인터넷 세계를 방랑한다. 편향된 정보가 입력되면 편향된 정보를 출력할 수밖에 없다. AI 이미지 생성기는 여성의 성적인 이미지를 부각하는 경향이 있다.

AI로부터 데이터를 어떻게 보호할 수 있을까

안타깝게도 현재 데이터를 의미 있게 보호할 수 있는 옵션은 거의 없다. AI 모델이 이미지를 효과적으로 읽을 수 없도록 만드는 데 사용할 수 있는 Glaze라는 도구가 개발됐지만, 일부 AI 이미지 생성기에서만 그 효과를 검증할 수 있었으며 용도도 제한적이다. 또한 온라인에 게시되지 않았던 이미지만 보호할 수 있다는 한계점도 있다. 텍스트의 경우 이와 유사한 도구가 존재하지 않는다. 웹 사이트 소유자는 웹 크롤러와 스크래퍼에게 사이트 데이터를 수집하지 말라는 디지털 플래그를 삽입 할 수 있다. 그러나 이러한 고지를 준수할지 여부는 스크래퍼 개발자의 선택에 달려 있다.

캘리포니아를 비롯한 몇몇 주에서는 최근 통과된 디지털 개인정보 보호법에 따라 소비자는 기업에 데이터 삭제를 요청할 수 있는 권리를 갖게 되었다. 유럽연합(EU)에서도 사람들은 데이터 삭제에 대한 권리를 가지고 있다. 그러나 지금까지 AI 기업들은 데이터의 출처를 증명할 수 없다고 주장하거나 요청을 아예 무시하는 방식으로 이러한 요청을 거부해 왔다고 스탠퍼드 대학의 개인정보 보호 및 데이터 연구원인 제니퍼 킹(Jennifer King)은 말했다. 기업이 데이터 삭제 요청을 이행하여 사용자의 정보를 학습 세트에서 제거하더라도 AI 모델이 이전에 흡수한 내용을 잊게 만드는 명확한 방법도 없는 실정이다.

AI 모델에서 저작권이 있거나 잠재적으로 민감한 정보를 모두 제거하려면 AI를 처음부터 재교육해야 하는데, 이 경우 최대 수천만 달러의 비용이 들 수 있다. 현재로서는 테크 기업이 재교육 조처를 하도록 요구하는 강력한 정책이나 법적 판결이 없으므로 그들이 다시 원점에서 시작해야 할 이유가 없는 상황이다.

Your Personal Information Is Probably Being Used to Train Generative AI Models

Companies are training their generative AI models on vast swathes of the Internet—and there’s no real way to stop them

Artists and writers are up in arms about generative artificial intelligence systems—understandably so. These machine learning models are only capable of pumping out images and text because they’ve been trained on mountains of real people’s creative work, much of it copyrighted. Major AI developers including OpenAI, Meta and Stability AI now face multiple lawsuits on this. Such legal claims are supported by independent analyses; in August, for instance, the Atlantic reported finding that Meta trained its large language model (LLM) in part on a data set called Books3, which contained more than 170,000 pirated and copyrighted books.

And training data sets for these models include more than books. In the rush to build and train ever-larger AI models, developers have swept up much of the searchable Internet. This not only has the potential to violate copyrights but also threatens the privacy of the billions of people who share information online. It also means that supposedly neutral models could be trained on biased data. A lack of corporate transparency makes it difficult to figure out exactly where companies are getting their training data—but Scientific American spoke with some AI experts who have a general idea.

WHERE DO AI TRAINING DATA COME FROM?

To build large generative AI models, developers turn to the public-facing Internet. But “there’s no one place where you can go download the Internet,” says Emily M. Bender, a linguist who studies computational linguistics and language technology at the University of Washington. Instead developers amass their training sets through automated tools that catalog and extract data from the Internet. Web “crawlers” travel from link to link indexing the location of information in a database, while Web “scrapers” download and extract that same information.

A very well-resourced company, such as Google’s owner, Alphabet, which already builds Web crawlers to power its search engine, can opt to employ its own tools for the task, says machine learning researcher Jesse Dodge of the nonprofit Allen Institute for AI. Other companies, however, turn to existing resources such as Common Crawl, which helped feed OpenAI’s GPT-3, or databases such as the Large-Scale Artificial Intelligence Open Network (LAION), which contains links to images and their accompanying captions. Neither Common Crawl nor LAION responded to requests for comment. Companies that want to use LAION as an AI resource (it was part of the training set for image generator Stable Diffusion, Dodge says) can follow these links but must download the content themselves.

Web crawlers and scrapers can easily access data from just about anywhere that’s not behind a login page. Social media profiles set to private aren’t included. But data that are viewable in a search engine or without logging into a site, such as a public LinkedIn profile, might still be vacuumed up, Dodge says. Then, he adds, “there’s the kinds of things that absolutely end up in these Web scrapes”—including blogs, personal webpages and company sites. This includes anything on popular photograph-sharing site Flickr, online marketplaces, voter registration databases, government webpages, Wikipedia, Reddit, research repositories, news outlets and academic institutions. Plus, there are pirated content compilations and Web archives, which often contain data that have since been removed from their original location on the Web. And scraped databases do not go away. “If there was text scraped from a public website in 2018, that’s forever going to be available, whether [the site or post has] been taken down or not,” Dodge notes.

Some data crawlers and scrapers are even able to get past paywalls (including Scientific American’s) by disguising themselves behind paid accounts, says Ben Zhao, a computer scientist at the University of Chicago. “You’d be surprised at how far these crawlers and model trainers are willing to go for more data,” Zhao says. Paywalled news sites were among the top data sources included in Google’s C4 database (used to train Google’s LLM T5 and Meta’s LLaMA), according to a joint analysis by the Washington Post and the Allen Institute.

Web scrapers can also hoover up surprising kinds of personal information of unclear origins. Zhao points to one particularly striking example where an artist discovered that a private diagnostic medical image of herself was included in the LAION database. Reporting from Ars Technica confirmed the artist’s account and that the same data set contained medical record photographs of thousands of other people as well. It’s impossible to know exactly how these images ended up being included in LAION, but Zhao points out that data get misplaced, privacy settings are often lax, and leaks and breaches are common. Information not intended for the public Internet ends up there all the time.

In addition to data from these Web scrapes, AI companies might purposefully incorporate other sources—including their own internal data—into their model training. OpenAI fine-tunes its models based on user interactions with its chatbots. Meta has said its latest AI was partially trained on public Facebook and Instagram posts. According to Elon Musk, the social media platform X (formerly known as Twitter) plans to do the same with its own users’ content. Amazon, too, says it will use voice data from customers’ Alexa conversations to train its new LLM.

But beyond these acknowledgements, companies have become increasingly cagey about revealing details on their data sets in recent months. Though Meta offered a general data breakdown in its technical paper on the first version of LLaMA, the release of LLaMA 2 a few months later included far less information. Google, too, didn’t specify its data sources in its recently released PaLM2 AI model, beyond saying that much more data were used to train PaLM2 than to train the original version of PaLM. OpenAI wrote that it would not disclose any details on its training data set or method for GPT-4, citing competition as a chief concern.

WHY ARE DODGY TRAINING DATA A PROBLEM?

AI models can regurgitate the same material that was used to train them—including sensitive personal data and copyrighted work. Many widely used generative AI models have blocks meant to prevent them from sharing identifying information about individuals, but researchers have repeatedly demonstrated ways to get around these restrictions. For creative workers, even when AI outputs don’t exactly qualify as plagiarism, Zhao says they can eat into paid opportunities by, for example, aping a specific artist’s unique visual techniques. But without transparency about data sources, it’s difficult to blame such outputs on the AI’s training; after all, it could be coincidentally “hallucinating” the problematic material.

A lack of transparency about training data also raises serious issues related to data bias, says Meredith Broussard, a data journalist who researches artificial intelligence at New York University. “We all know there is wonderful stuff on the Internet, and there is extremely toxic material on the Internet,” she says. Data sets such as Common Crawl, for instance, include white supremacist websites and hate speech. Even less extreme sources of data contain content that promotes stereotypes. Plus, there’s a lot of pornography online. As a result, Broussard points out, AI image generators tend to produce sexualized images of women. “It’s bias in, bias out,” she says.

Bender echoes this concern and points out that the bias goes even deeper—down to who can post content to the Internet in the first place. “That is going to skew wealthy, skew Western, skew towards certain age groups, and so on,” she says. Online harassment compounds the problem by forcing marginalized groups out of some online spaces, Bender adds. This means data scraped from the Internet fail to represent the full diversity of the real world. It’s hard to understand the value and appropriate application of a technology so steeped in skewed information, Bender says, especially if companies aren’t forthright about potential sources of bias.

HOW CAN YOU PROTECT YOUR DATA FROM AI?

Unfortunately, there are currently very few options for meaningfully keeping data out of the maws of AI models. Zhao and his colleagues have developed a tool called Glaze, which can be used to make images effectively unreadable to AI models. But the researchers have only been able to test its efficacy with a subset of AI image generators, and its uses are limited. For one thing, it can only protect images that haven’t previously been posted online. Anything else may have already been vacuumed up into Web scrapes and training data sets. As for text, no such similar tool exists.

Website owners can insert digital flags telling Web crawlers and scrapers to not collect site data, Zhao says. It’s up to the scraper developer, however, to opt to abide by these notices.

In California and a handful of other states, recently passed digital privacy laws give consumers the right to request that companies delete their data. In the European Union, too, people have the right to data deletion. So far, however, AI companies have pushed back on such requests by claiming the provenance of the data can’t be proven—or by ignoring the requests altogether—says Jennifer King, a privacy and data researcher at Stanford University.

Even if companies respect such requests and remove your information from a training set, there’s no clear strategy for getting an AI model to unlearn what it has previously absorbed, Zhao says. To truly pull all the copyrighted or potentially sensitive information out of these AI models, one would have to effectively retrain the AI from scratch, which can cost up to tens of millions of dollars, Dodge says.

Currently there are no significant AI policies or legal rulings that would require tech companies to take such actions—and that means they have no incentive to go back to the drawing board.