中 빅테크 기업, 과도한 기술 규제로 기업가정신 사라져

알리바바, 2020년 IPO 취소 이후 기업가치 70% 하락 중국판 우버 디디추싱도 뉴욕증시 상장 1년 만에 상폐 빅테크 기업의 비즈니스 모델 변화로 중국 경제 타격

[동아시아포럼]은 EAST ASIA FORUM에서 전하는 동아시아 정책 동향을 담았습니다. EAST ASIA FORUM은 오스트레일리아 국립대학교(Australia National University) 크로퍼드 공공정책대학(Crawford School of Public Policy) 산하의 공공정책과 관련된 정치, 경제, 비즈니스, 법률, 안보, 국제관계에 대한 연구·분석 플랫폼입니다. 저희 폴리시코리아(The Policy Korea)와 영어 원문 공개 조건으로 콘텐츠 제휴가 진행 중입니다.

지난 2020년 11월 알리바바 그룹 계열사인 앤트그룹(Ant Group)의 기업공개(IPO) 취소를 시작으로 기술 규제를 강화해 온 중국 정부가 올해 들어 주요 빅테크 기업들에 대한 규제 완화를 시사하고 있다.

시진핑 주석, 공동부유 강조하며 기술 규제 강화

지난 2020년 하반기부터 시진핑 국가주석은 ‘공동부유’를 국정 기조로 내세워 자국의 빅테크 기업에 대한 전방위 압박에 착수했다. 이후 2년간 중국 정부는 디지털 기업의 독과점과 인수합병(M&A), 금융 진출 등을 강력히 규제했고 이같은 조치는 앤트그룹 외에도 여러 빅테크 기업들에게 영향을 미쳤다. 실제 알리바바, 텐센트, 징둥닷컴 등 중국의 빅테크 기업들은 정부의 방역 정책과 전방위 견제로 인해 지난해 1분기 사상 최저 매출을 기록했다.

하지만 코로나19 이후 중국의 경기 둔화가 장기화되면서 중국 정부는 올해 들어 플랫폼 기업들에 대한 기술 규제를 완화 기조로 전환했다. 최근 중국은 지난 3년간 이어온 ‘제로 코로나’ 정책을 폐지했음에도 경기 회복세가 당초 예상에 크게 못 미치고 있다. 중국의 16∼24세 청년실업률은 지난 3월 19.6%를 기록한 이후 3개월 연속 20%를 넘어서며 관련 통계 작성 이후 사상 최고치를 경신했고, 지난 6월에는 전월 대비 0.5%p 오른 21.3%를 기록했다. 급기야 중국 정부는 7월부터 연령대별 실업률 발표를 중단했다.

지난 3월 중국개발포럼(China Development Forum)에 참석한 리창 총리는 글로벌 다국적 기업의 CEO들에게 “앞으로 중국은 세계 경제의 회복과 성장에 강한 역동성을 부여하는 동시에 전 세계 투자자에게 상호 이익과 상생의 기회를 제공할 것”이라며 개혁과 개방을 강조한 바 있다. 하지만 전문가들은 중국 정부의 기조 변화가 단순히 중국 경제 위기론에 대응한 조치가 아니라고 봤다. 실상은 지난 2년간의 전방위적 압박으로 인해 당초 중국 정부가 설정한 목표를 대부분 달성했기 때문이라고 해석했다.

정부 기술 규제로 인해 빅테크들 기업가치 하락

중국 정부가 기술 규제를 하는 진의에 대해서는 학계와 언론 사이에 다양한 의견이 나오고 있다. 일각에서는 알리바바의 설립자 마윈(Jack Ma)의 과도한 열정과 개성이 시진핑 국가주석의 마오주의 지향성과 충돌해 발생한 것이라고 주장하고 있다. 하지만 중국 정부의 기술 규제는 비단 알리바바와 마윈에만 국한되지 않았다는 점을 간과해선 안 된다. 이 때문에 일부 언론에서는 민영기업에 대해 적대적인 태도를 가지고 있는 시진핑 주석이 빅테크 분야의 민영기업을 국유화하기 위한 시도라는 주장이 제기됐다. 하지만 여전히 대형 민영기업들이 중국 시장에서 성장하고 있다는 점을 고려할 때 이러한 주장도 다소 과장된 것으로 보인다.

또 다른 관점에서는 중국 정부의 조치들을 단순히 엄격한 규제의 시행으로 보기보다는 정치적 이념의 관점에서 해석해야 한다는 의견도 있다. 중국 정부 입장에서는 민영기업의 성장으로 촉발된 자본주의가 무질서하게 확장되는 상황에서 그동안 시진핑 주석이 강조해 온 ‘공동부유’ 캠페인의 목표를 달성하기 위해 강력한 기술 규제가 필요했다는 해석이다.

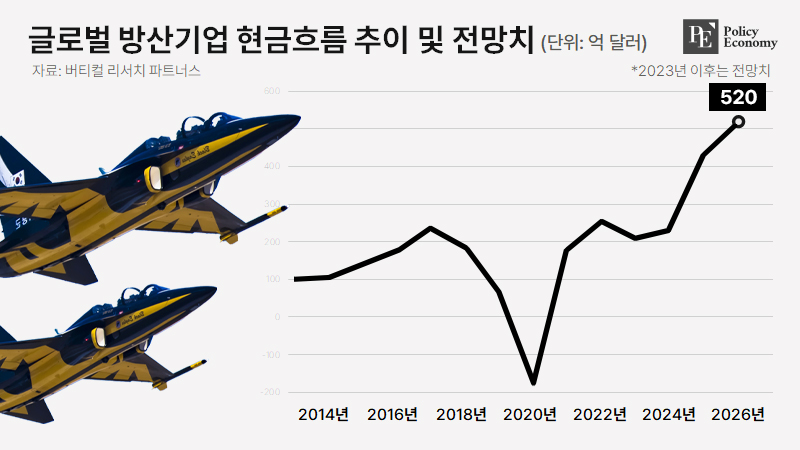

지난 2년간 중국의 과도한 규제로 인해 중국의 빅테크 기업들의 주주 이익이 훼손되고 기업가치가 현저히 떨어졌다. 일례로 지난 2020년 11월 3,130억 달러(약 400조원) 규모의 IPO를 준비했던 앤트그룹은 올해 7월, 당시보다 70% 하락한 금액에 자사주를 매입했다. 글로벌 차량공유 서비스 기업 디디추싱(Didi Chuxing)도 2021년 6월 뉴욕증시 IPO 당시 기업가치가 700억 달러(약 90조원)에 달했지만 1년 만에 상장 폐지되면서 현재는 시가총액 167억 달러(약 210조원)에 머물고 있다.

과도한 벌금 부과 등 빅테크 기업의 수익 국유화

기술 규제의 또 다른 목적은 빅테크 기업들이 해외에서 상장하거나 자산을 이전함으로써 발생하는 국부 유출을 막고 이들의 수익을 국가로 환수하는 데 있다. 이를 위해 중국 정부는 빅테크 기업들에게 전례 없이 높은 벌금을 부과했다. 실제 2021년 4월 중국 정부는 알리바바에 반독점법 위반으로 27억5,000만 달러(약 3조원)에 달하는 벌금을 부과한 바 있다. 앞서 같은 해 3월에는 텐센트, 바이두, 디디추싱, 소프트뱅크, 바이트댄스 등 12개 기업에 대해 반독점법 위반 혐의로 벌금을 부과하기도 했다.

중국 정부가 빅테크 기업의 수익을 환수하는 또 하나의 방법으로 시진핑 주석이 강조하는 ‘자발적인 기부’가 있다. 지난 2021년 시진핑 주석이 함께 부자가 되자는 공동부유 캠페인을 발표하자마자 중국 빅테크 기업들의 기부 릴레이가 이어졌고 텐센트는 공동부유 기금에 77억5,000만 달러(약 9조2,200억원)를 기부하기로 약정했다. 이외에도 중국 정부는 민영기업의 자본을 끌어모으기 위해 기업의 성장을 제한하는 전략을 사용하고 있다. 이러한 맥락에서 중국 정부는 뉴욕 증시에 상장된 디디추싱에 대해 개인정보 유출을 문제 삼아 18개월간 신규 사용자 등록을 금지했고 이 기간 국영기업인 화웨이 등 경쟁 업체들이 차량 호출 서비스 시장에 진출했다.

일련의 기술 규제 조치는 중국 빅테크 기업의 경영 구조에 큰 변화를 가져왔다. 중국 정부는 이들 기업에 자신들이 지명한 이사를 임명하게 하고, 국영기업에 ‘황금주(golden shares)’를 발행하도록 강요했다. 황금주는 보유 수량이나 비율에 관계없이 주주총회 안건에 대해 거부권을 행사할 수 있는 권리를 가진 주식으로, 일반적으로 계열사 자본의 1% 수준에 불과하지만 기업의 경영에 막대한 영향을 끼칠 수 있다. 중국 정부는 황금주를 통해 민영기업의 전략적 결정에 대해 거부권을 행사하는 등 강력한 영향력을 행사하는 도구로 활용하고 있는 것이다.

앤트그룹 IPO 취소, 마윈 해임 등 민간부문 혼란

무엇보다 기술 규제로 인한 가장 중대한 변화 중 하나는 기업가정신의 상징과도 같았던 마윈의 해임이다. 앤트그룹의 IPO가 무기한 연장되면서 마윈은 사실상 경영 일선에서 물러났다. 지난 7월 앤트그룹은 주주회의에서 지분 재조정을 논의한 결과 마윈의 의결권을 당초 50.0%에서 6.2%로 줄이는 데 합의했다고 밝혔다.

지난 2년간 중국의 빅테크 기업들은 정부의 강력한 규제를 버텨냈다. 하지만 이 과정에서 비즈니스 모델의 변화를 감수해야만 했다. 기술 규제가 시작된 2020년 11월 이전까지 중국의 빅테크 기업들은 일반적인 중국 대기업들과는 매우 다르게 운영되고 있었다. 당시 이들의 비즈니스 모델은 기업가정신에 기반한 것으로 완전한 민영화 속에서 글로벌 벤처캐피탈(VC)의 지원을 받았고, 주주 가치 극대화를 추구하는 헌신적인 리더가 존재했다. 하지만 이제 이같은 기업가적 비즈니스 모델은 소멸됐다. 대신 한때 혁신적이었던 이 기업들은 시장에서 정부의 영향력을 보장하는 동시에 사실상 국가로부터 지배를 받는 중국의 대기업들과 조화를 이뤄야만 한다.

기술 규제로 인한 혼란과 빅테크 기업의 비즈니스 모델 변화는 중국 경제의 민간 부문에 심각한 타격을 줬다. 특히 중국 정부가 마윈과 같은 기업가에게 자신이 설립한 기업에 대한 통제 권한을 박탈한 사례는 민간 부문에서 부정적인 정서를 야기함으로써 향후 중국의 혁신기업들의 성장을 가로막는 요인이 될 가능성이 있다. 물론 이러한 부정적 정서는 향후 개선될 여지가 있다. 하지만 현재 중국 경제의 위기론이 대두된 상황에서 그동안 이어져 온 빅테크 기업에 대한 강력한 규제와 전방위적 압박은 거시경제 측면에서 부정적인 요인으로 작용하고 있다.

Tech crackdowns rid China of entrepreneurial capitalism

Since early 2023, Chinese authorities have started extending an olive branch to China’s top platform tech companies after over two years of ‘regulatory crackdown’. The crackdown started in November 2020 with the cancellation of the initial public offering (IPO) of e-commerce giant Ant Group — an affiliate of Alibaba.

Besides Ant Group, the ‘rectification’ affected most of China’s large platform companies. Yet by June 2023, a cold was blowing over China’s economy. The post-COVID-19 recovery was faltering. Youth unemployment rose above 21 percent.

The authorities also likely concluded that they had accomplished most of the objectives of the rectification. At the China Development Forum in March 2023, Premier Li Qiang bent over backwards to assure prominent Western CEOs that China was welcoming the private sector, both foreign and domestic.

There is no consensus among academic and journalistic commentators about the crackdown’s ‘true’ objectives. One view holds that it was a personality clash between the ‘exuberance’ of Jack Ma — Alibaba’s founder and China’s most prominent private entrepreneur — and the fundamentally Maoist orientation of President Xi Jinping.

But a focus on Jack Ma ignores the fact that essentially all platform companies underwent some form of rectification. Another view holds that it was simply a scheme to clip the wings of China’s top private companies, given Xi Jinping’s embrace of the state-owned sector. Yet data showing an increasing penetration of China’s economy by large private companies belied Xi Jinping’s alleged hostility to the private sector.

Others maintain that a ‘great’ rectification was needed to align the mission of platform tech companies with Xi Jinping’s social policy objectives such as ‘common prosperity’ and the drive against ‘disorderly expansion of capital’. But the true objective of the crackdown had little to do with regulation, as authorities’ actions went beyond what might be considered an imposition of a stricter regulation.

Regulatory rectification was only a vehicle to accomplish other objectives. The crackdown was characterised by a spate of shareholder wealth destruction. Ant Group was headed for its IPO in November 2020 at an implied valuation of US$313 billion. Yet in July 2023, Ant Group launched a share buyback at a valuation that was 70 per cent lower. The global ride-sharing leader, Didi Chuxing, conducted its New York IPO in June 2021 at a valuation of US$70 billion. After a forced delisting from the New York Stock Exchange, it is currently trading over the counter with a market capitalisation of about US$16.7 billion.

The other side of the coin was the wealth extraction from platform companies to various state-owned entities. One instrument of extraction was in the form of unprecedented fines. Alibaba was fined US$2.8 billion in April 2021 for alleged abuse of market dominance.

Another method of extraction was through ‘voluntary’ contributions to causes championed by Xi Jinping. Tencent — the global game leader and investor in many start-ups — ‘earmarked’ US$7.7 billion in 2021 to a fund dedicated to ‘common prosperity’.

Another extraction mechanism was carried out through putting a brake on platform companies’ ability to grow. Didi was barred from registering new users for 18 months. This conveniently opened a market window for several of Didi’s state-backed competitors such as Huawei Technologies of T3 Chuxing.

A major effect of the crackdown has been a fundamental change in corporate governance. Platform tech companies have been forced into appointing state-nominated directors and issuing ‘golden shares’ in subsidiary companies to state-owned enterprises under joint venture partnerships. Such golden shares amount typically to only about 1 per cent of a subsidiary’s equity. But they bestow disproportionate corporate governance rights upon the minority shareholders. The state has acquired veto power over strategic decisions in those companies.

Probably the most momentous corporate governance upheaval was the defenestration of Jack Ma — the symbol of China’s entrepreneurial success. Jack Ma was effectively banished upon the cancellation of Ant Group’s IPO. The company was subjected to a share reshuffling which shrank Jack Ma’s voting rights from over 50 per cent to 6.2 per cent.

Platform companies have survived the regulatory crackdown. But they do so at the price of an irreversible change in their business models. Before November 2020, those companies were very different from most of China’s large private companies. Their business model at that time could be described as ‘entrepreneurial’ — completely private, backed by world-class venture capital and guided by entrepreneurial leaders dedicated to shareholder value maximisation.

This entrepreneurial business model has now been extinguished. Instead, these firms must align with other large private Chinese companies which tend to be intertwined with the state. This ensures significant state influence over the private sector.

The business model upheaval has also fuelled a massive blow to sentiment in China’s private sector. For a Chinese private company owner, it is difficult to feel upbeat if the authorities can deprive a top private entrepreneur — such as Jack Ma — of control rights over the company he or she has founded.

Sentiment might improve in the future. But for the time being, the regulatory crackdown will remain a major contributor to China’s stumbling macroeconomic performance.

원문의 저자는 중국인민대학교(Renmin University) 경영대학원의 마틴 미제락(Martin Miszerak) 방문 교수입니다.